One in three seniors aging into Medicare over the next 10 years will be people of color, and this trend to greater diversity in Medicare will only continue. Not all counties in the U.S. experienced a change in the percent of non-white residents since 2010, but almost all that did saw that population increasing.[1] Currently, 24% of seniors age 65+ in the US are something other than Non-Hispanic White alone (NHW).

While this trend is nothing new, the Medicare industry may find themselves increasingly needing to walk a very fine line of focusing certain aspects of insurance and patient care to a particular race or ethnicity without alienating anyone else. For example, coverage for acupuncture may be popular and expected by one demographic group, but others may feel this is not the best way for “their” Medicare dollars to be spent. Navigating race is not an easy task in the best of times, and with the increase in protests following George Floyd’s death and a rise in anti-Asian racism, just to name a few, these past few years have been anything but that.

Racial disparity in patient care is well documented by the US Department of Health and Human Services and by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Not only is addressing unequal health care the right thing to do, for insurance carriers specifically this gap in care can directly affect CAHPS and carrier shopping and switching. If some groups feel less “seen” by their insurer, they may feel less inclined to provide the highest ratings.

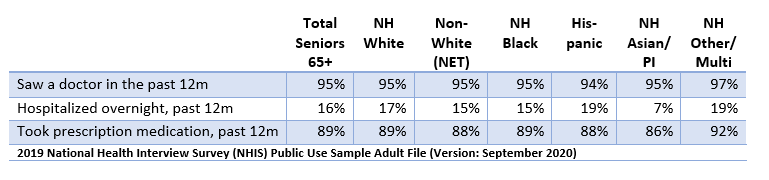

Black/African American seniors found their patient experience in Medicare Advantage to be similar to NHWs, but have worse outcomes across many different conditions, including issues controlling high blood pressure, having continuous beta-blocker treatment after a heart attack and diabetes care.[1] While the vast majority (95%) have seen a doctor in the past 12 months just like their NHW counterparts, Black seniors are more likely than NHW seniors to have visited an ER or urgent care as well, resulting in a higher cost for care.[2] At age 65, Black seniors have a life expectancy of 81.5 years, while NHW seniors will average 2.6 more years (84.1 years).[3] The full effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on life expectancy in the Black community and others remain to be seen– the gap could widen further.

Asian and Pacific Islander seniors rate their Medicare Advantage patient experience worse than NHWs on many measures, including some surrounding communication (e.g. customer service, doctors who communicate well, and care coordination).[4] Only 46% of Asian/PI seniors speak English only or very well. This is similar to Hispanic/ Latino seniors—half speak English only or very well—but Spanish is a very common language when compared to the myriad of Asian languages spoken in the US. Even knowing the top FIVE languages spoken by Asian/PI seniors (Chinese, English, Filipino/Tagalog, Hindi and Vietnamese) would still leave a full 20% of Asian seniors unable to communicate with their doctor.[5] Despite communication issues, Asian/PI seniors are healthier than their NHW counterparts. They are less likely to have needed an urgent care or ER visit in the past 12 months, and only 7% were hospitalized overnight in past year, comparted to 15% of NHWs.[6]

Hispanic/Latino seniors rate their access to Medicare Advantage health care lower than NHW seniors, saying they had issues getting the care they needed and getting it quickly.[7] This might be because some (not a majority at all, but just enough to cause noticeable differences) underutilize primary health care until it becomes urgent and unavoidable. For example, once they are 65+, 94% of Hispanics have seen a doctor in the past 12 months (compared to 95% of NHWs). However, when looking at a slightly younger cohort (55-64) the gap widens to 86% of Hispanics vs. 89% of NHWs. After age 64, Hispanics are more likely to have visited urgent care and the ER than NHWs.[8]

[1] Racial, Ethnic, & Gender Disparities in Health Care in Medicare Advantage, CMS, April 2021 [2] NHIS 2019 data set [3] https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/VSRR10-508.pdf, page 2 [4] Racial, Ethnic, & Gender Disparities in Health Care in Medicare Advantage, CMS, April 2021 [5] ACS 2019 1-year estimates from IPUMS.org [6] NHIS 2019 data set [7] Racial, Ethnic, & Gender Disparities in Health Care in Medicare Advantage, CMS, April 2021 [8] NHIS 2019 data set