Creating the most effective marketing campaign is a challenge. It is made more difficult when marketing teams must make decisions without input from consumers. Part of the creative mystique is having the insight into human nature and the good taste to know what will work. But in many situations, the genius of the marketing team is not tested by real measurement and so we never know what works best and what might have worked better. Since the rollout of a marketing campaign requires the commitment of millions of dollars by the marketing organization, testing marketing concepts ahead of time seems like a good idea for validating perceptions and assuring a satisfactory return on this investment.

![]() The traditional idea of treating a promotional piece as whole cloth leads us to think of testing two or more versions of a promotion in an attempt to determine which version is most likely to generate the desired consumer response – this is known as A/B testing. While often standard procedure, A/B testing sometimes fails because it doesn’t yield meaningfully different measures of version performance. The failure of A/B testing to help distinguish a winning version leads teams back to reliance on the judgment of a small group of decision makers.

The traditional idea of treating a promotional piece as whole cloth leads us to think of testing two or more versions of a promotion in an attempt to determine which version is most likely to generate the desired consumer response – this is known as A/B testing. While often standard procedure, A/B testing sometimes fails because it doesn’t yield meaningfully different measures of version performance. The failure of A/B testing to help distinguish a winning version leads teams back to reliance on the judgment of a small group of decision makers.

![]() Deft Research has developed a testing approach based on Conjoint analysis that measures the relative impact of each component of a promotion. Conjoint analysis has been used extensively in package design research. Here, Deft has adapted this methodology to testing health insurance advertising.

Deft Research has developed a testing approach based on Conjoint analysis that measures the relative impact of each component of a promotion. Conjoint analysis has been used extensively in package design research. Here, Deft has adapted this methodology to testing health insurance advertising.

This approach enables us to measure each component’s contribution to the overall impact so that the most effective components can be brought together by the creative team. It shows the most effective combinations of components and how that effectiveness varies between different market segments.

![]() To accomplish one of these studies, a survey is programmed that allows different versions of each promotional component to be displayed in varying combinations to consumers. Consumers then respond to side-by-side combinations and are asked to indicate to which ad they are most likely to respond. Research objectives can focus on building brand awareness and impression, or generating interest (want to know more), or motivation to act (click on a link, or call the 800 number, etc.)

To accomplish one of these studies, a survey is programmed that allows different versions of each promotional component to be displayed in varying combinations to consumers. Consumers then respond to side-by-side combinations and are asked to indicate to which ad they are most likely to respond. Research objectives can focus on building brand awareness and impression, or generating interest (want to know more), or motivation to act (click on a link, or call the 800 number, etc.)

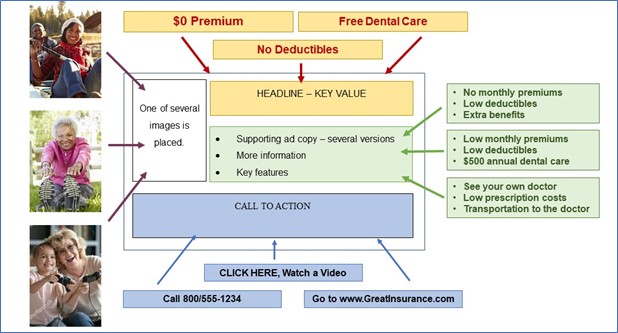

![]() The programmed survey pulls layouts, images, headlines, ad copy, and calls to action from several proposed promotions into computer generated “versions”.

The programmed survey pulls layouts, images, headlines, ad copy, and calls to action from several proposed promotions into computer generated “versions”.

Diagram: several versions of each component can be put together in any combination.

A study like this can test hundreds of versions and generate tens of thousands of consumer responses. The outcome of such research is a measurement of the appeal or effectiveness of each version of each component. With this information, researchers and marketing teams can assemble the ideal combinations.

We may recommend research designs that use traditional survey questions, Max-Diff exercises, or conjoint analysis to accomplish the goals of the client.

Our client wanted to supplement their current understanding of marketing effectiveness by testing ad versions for brand recall and product uniqueness. Understanding these aspects of promotions was deemed critical to the next year’s success.

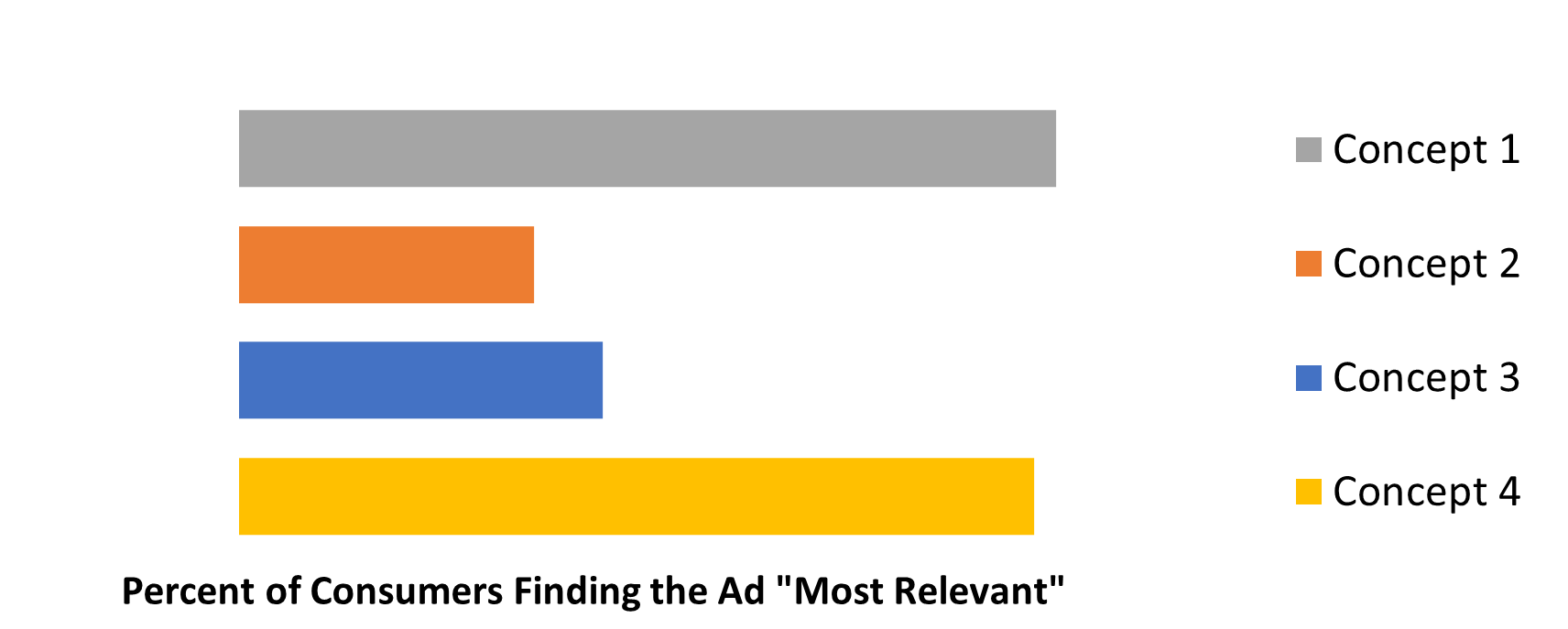

Based in the client’s needs, we developed a conjoint based testing study. The objectives of the study were to test four different advertising concepts along five different dimensions:

Of the four tested concepts, winners emerged.

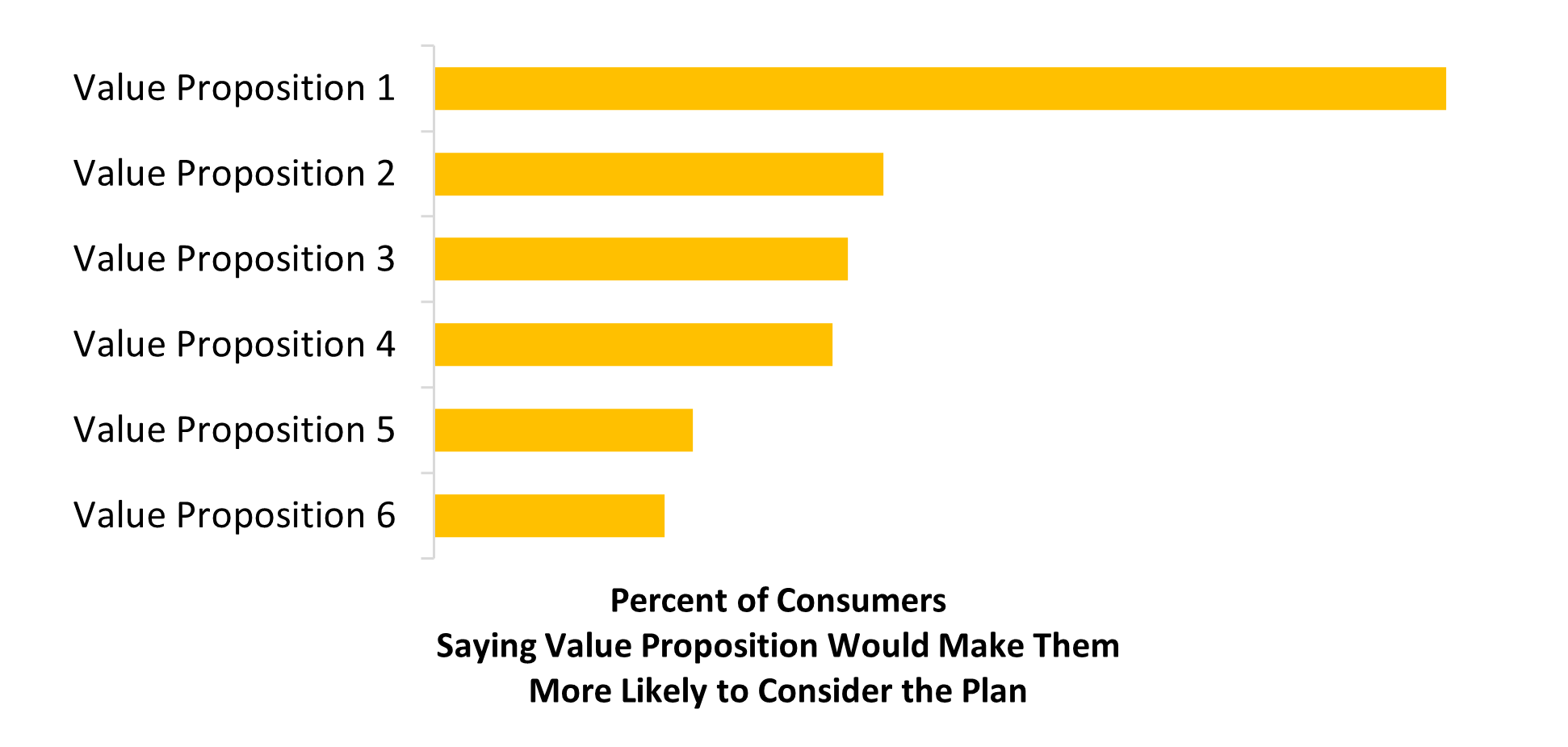

After the initial concepts were tested, a further analysis tested separate components for their impact on likelihood to consider a health plan.

Analysis revealed a single most preferred ad copy.

Conjoint analysis is a flexible method that allows the interests of the client to dictate what is measured. In this article we have provided several ideas about how imagery, headline, ad copy, and calls-to-action can be measured for their impact on consumers. The consumer impact can be measured along one or more dimensions – for example, relevance, likelihood to consider, likelihood to perform a call-to-action and others.