In previous blog posts we outlined the role of social factors and frames of reference in health outcomes and as factors in communicating with patients.

In this article, we focus on the use of the emergency room by some patients for non-emergency and routine medical care. We develop the term “Convenience ER Use” to refer to this.

Transportation to doctor appointments, engage health, population health

With respect to using the term “convenience” to describe ER use, we use the following definition,

“Convenient services are those which, compared to alternatives, are easy to access, use time and other resources efficiently, and decrease frustration.”

We use the word “convenience” in this sense to suggest that a subset of patients perceive the ER as their most convenient venue among their choices for medical care. No negative connotation is intended or implied.

It has been estimated that two thirds of Americans say that they would go to the ER if they could not see their primary care doctor and three quarters say that going to the ER is easier than getting an appointment to see their doctor (1).

In a recent report, UnitedHealth Group examined the diagnostic outcomes of all 2018 ER claims under UnitedHealthcare employer sponsored coverage. They estimated that about two thirds of these cases were avoidable and could have been treated in either urgent care or primary care offices for less than 10% of the cost. Based on CDC reports and average ER, urgent care, and primary care costs, the UnitedHealth Group analysis says that as many as 18 million ER cases per year are avoidable, and that moving these cases to less costly venues could save as much as $32 billion annually (2).

We wanted to create an estimate that accounted for legitimate false alarms, something the UHC analysis did not do.

The optimal outcome for ER visits is the doctor’s reassurance, “False alarm. Don’t worry, you’re going to be OK.” Unless we expect the patient to be the diagnostician, it seems reasonable for some proportion of ER visits to turn out to be legitimate false alarms. Given this reasoning, we pursued our own estimate.

In our recent study of people with non-employer sponsored health coverage, we surveyed 3,424 consumers aged 19-64 who were either uninsured or covered by Medicaid or Individual-Family plans (under the ACA). We asked two questions related to ER visits:

1. Have you experienced severe personal injury or illness in the past 12 months?

2. In the past year, how many times have you visited the Emergency Room (E.R.)?

Using these questions, we judged that those respondents who visited the ER just once in the absence of severe injury or illness, may have had a “false alarm” (legitimate emergency concerns but a non-emergency outcome). But those who did so multiple times were routinely using the ER for non-emergency purposes. We call this latter group “Convenience ER Users”.

We double checked this classification and confirmed with two findings.

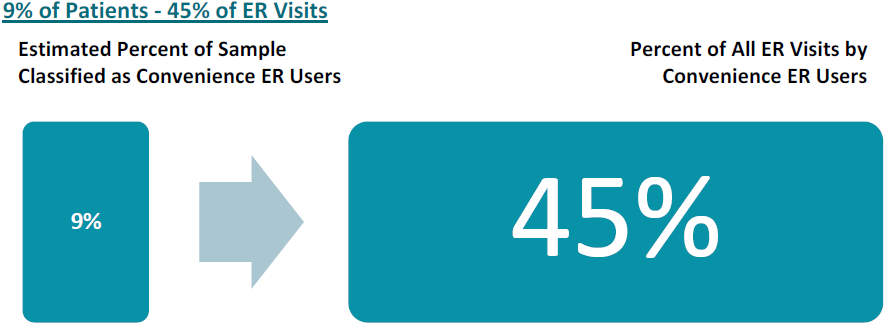

While Convenience ER Users represent 9% of the study’s sample, we estimate that they account for 45% of visits to Emergency Rooms.

A primary concern of health system managers is to find ways to steer Convenience ER Users toward lower-cost care settings such as primary care physicians and clinics. In order to shed some light, we looked at who the Convenience ER Users are and examined some of the social factors and frames of reference that might lead them to use the ER rather than a lower cost setting.

The study does not support the idea that lower income leads to Convenience ER Use.

Of course, it is widely known that people on Medicaid and the uninsured have lower incomes and also are more likely to use emergency rooms.

But if we look at Convenience ER Use only within insurance group, household income does not seem to be a driver. In other words, despite a fairly large income range, privately insured Convenience ER Users were not poorer than privately insured users who did not use the ER. The same was true for the uninsured. Moreover, Convenience ER Users were not any more likely to say they had declined medical care because of cost. Motivation to use the ER appears to be about more than sensitivity to out-of-pocket costs.

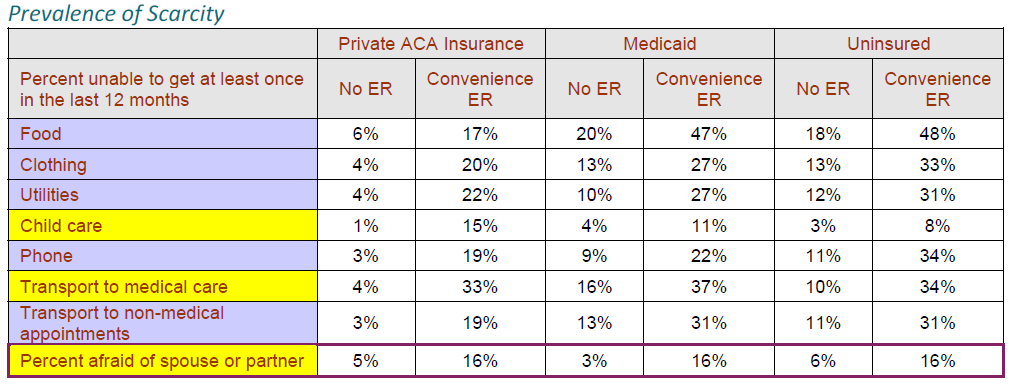

The presence of scarcity is the most distinguishing social factor associated with Convenience ER Users. Convenience ER users were much more likely to report that they or their families had been unable to get at least one needed item (e.g., food, clothing, utilities) at some point in the last year.

Obtaining Child Care. Convenience ER users who are members of individual and family insurance plans were 15 times more likely than non-ER Users to say that they were unable to access childcare in the last year (15% vs 1%). Medicaid or uninsured Convenience ER users were nearly three times as likely as non-ER users to report being unable to access childcare (9% vs 3%).

Lack of Transportation. Over a third of Convenience ER Users said that lack of transportation kept them from medical appointments at some point during the previous year. Among those with private health insurance the difference was dramatic. Convenience ER Users with IFP insurance were 9 times more likely to say that lack of transportation kept them from medical appointments (33% vs 4%).

Lack of Personal Security. Convenience ER users are much more likely than others to feel emotionally and physically unsafe in their living conditions. Those who used the ER multiple times in the absence of a severe injury or illness were much more likely to report that they had been afraid of a spouse or ex-spouse within the past year – this was not limited to women only.

Our analysis has illuminated how regardless of household income, lack of social support when needed can lead to non-emergency use of ER’s.

These results emphasize the value of providing:

Providing ways for people to overcome these obstacles could help reduce the excess health care costs that arise from non-emergency use of emergency rooms. These measures would have their greatest impact on the adverse financials of Medicaid and uninsured populations where reimbursement is often below the cost of care, or there is no reimbursement at all for the health services provided.

1. Study: Nearly 3 in 4 Americans Say It’s Easier to Go to the ER Than to Get a Doctor’s Appointment https://www.zocdoc.com/about/news/2019-er-report/

2. UnitedHealthcare analysis conducted in 2019 of U.S. commercial claims from 2018. https://www.unitedhealthgroup.com/content/dam/UHG/PDF/2019/UHG-Avoidable-ED-Visits-citations.pdf